Institute News, Uncategorized

Dear Members, firstly, may l add my own welcome and best wishes for the year ahead to all our membership, wherever you may be based. ICorr is expanding Internationally and will continually seek to find ways to serve you in your work, in a friendly and accessible manner.

I am deeply honoured to have been elected to serve you as your President for the next 2 years and to follow in the footsteps of Dr Bill Hedges, who has laid very solid foundations for the Institute going forwards and guided me diligently throughout my vice Presidency. I am also very appreciative of all the goodwill messages l have received from you in recent weeks.

Particular thanks are due to my colleagues of ICorr Aberdeen committee, who have supported me extremely well over the last 10 years in my various roles as Chair, Vice Chair and Secretary. Dr Yunnan Gao, also a previous branch chair will join me as vice President along with Bill as our Immediate Past President, who have vast industry experience. This combined experience has been invaluable in preparing me for my new daily duties as your President and as a member of ICorr Council and its board of Trustees.

I expect by the time you receive this latest edition of the magazine, which sadly may be the very last by our current editor Brian Goldie, we shall be well into the first chapter of 2023 but many more Institute activities still await us through our YICorr organisation, across all our regional branches, and operating divisions.

Over the next few weeks and months, I’ll be meeting teams and visiting our branches to gain a deeper understanding of ICorr. I am really looking forward to spending time with you, learning more about our operating divisions, what is working well, and listening to your ideas and suggestions, around where we can make enhancements together.

We have already made a fantastic start to the year with the signing of our new 10year training agreement in January with IMechE to deliver ICorr developed courses globally along with Corrodere who continue to support us with our online training course delivery, plus Square One, and Eva Whittaker’s great work in modernising our CP course bookings system.

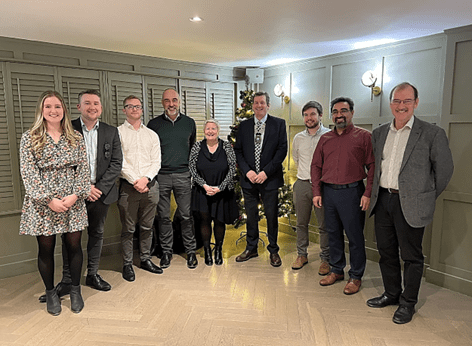

It was a great pleasure recently to meet with our branch members at the London Branch luncheon in December, a fantastic event as always. Also, to meet with committee members from our reactivated North-East branch in Newcastle, and to see both of these in-person events so well supported. The YICorr Xmas quiz was a great closer to a very active year which included a spectacular Young Engineer Programme final in Aberdeen. Many congratulations to Team 5 on their success.

Please do use all available opportunities to network with ICorr, to learn more about us, learn about each other, and the industries that we all work to serve.

Our Birmingham 1-Day conference on February 9th will bring together many of our award winners, several of our sustaining companies and training providers, in the splendid setting of the City Chambers. April 27th will take us to NPL, Teddington, for four Corrosion Engineering Division Working Day, and June 22nd and 23rd will feature our main 2-day Sustainability and Renewables Conference. August 29th will again see Aberdeen host its well-respected annual 1-day Corrosion Awareness event.

At ICorr HQ our staff – Denise Aldous, Becky Hurst, Patricia Bridge, Melanie Dunn, and Maureen Spittles, will be very active supporting you, and hosting several new ICorr training courses, ICATS seminars and examinations, throughout the year.

Our Hybrid technical programmes will continue over the coming months. Do please check regularly the ICorr Website, Upcoming Events – Institute of Corrosion (icorr.org) and ICorr News – Industry Updates – Institute of Corrosion (icorr.org).

Corrosion management and prevention remains a very specialised field with many sub disciplines, some of which we will strive to become operating experts in, and others that we require a sound understanding of their principles, to engage with others constructively for the preservation of our infrastructure.

ICorr through its activities, seeks to provide a sound and safe basis to all those following careers in corrosion, at all levels and to provide opportunities for advancement to all.

I sincerely hope that you will join me on my journey over the 2 years and l of course welcome any of your suggestions, do please contact me on any aspect of the Institute’s work at, president@icorr.org

With my very best wishes for the weeks and months ahead.

Stephen Tate

President: Institute of Corrosion

Institute of

Corrosion

President,

Stephen Tate.

Ask the Expert

Question:

When should you use corrosion resistant alloys in upstream production? CM

Answer:

This is a wonderfully simple question that does not have a simple answer. Corrosion Resistant Alloys can be an excellent material choice for combatting corrosion and they are an important addition to the options that we have as Materials and Corrosion (M&C) professionals. However, as with all materials there are pros and cons and it is the role of M&C engineers to evaluate the best option.

It is important that we recognise that when we talk about a Corrosion Resistant Alloy (CRA) we are referring to a specific metal or alloy that is resistant to a specific corrosion mechanism or mechanisms. For example, in Upstream operations, for some applications,316L stainless steel is increasingly used for its resistance to carbon dioxide (CO2) corrosion, and can be considered a CRA for this threat. However, this alloy is vulnerable to corrosion in oxygenated sea water and so is not a good material for this environment. So before selecting a corrosion resistant material, in additional to many other parameters, it is very important we define the corrosion mechanism or mechanisms that it needs to resist – on both the internal and external surfaces of the equipment.As in the example above many CRA’s are stainless steels, and historically the term “stainless steel” was used generically to indicate corrosion resistant metals. The term CRA emerged when alloys that do not have iron (Fe) as their majority element started to be used, e.g. nickel and titanium based alloys.

For our colleagues who are not M&C engineers, the term CRA can be misleading because there is no metal or alloy that is immune to every corrosion environment. To make this point I have sometimes joked that CRA should mean “Can Rust Actually”. A key role of M&C engineers is to educate colleagues on the limits of CRA’s in particular environments.

A further consideration when selecting a CRA is that we do not eliminate one corrosion mechanism only for it to be replaced by another. For example many stainless steels are resistant to CO2 corrosion but vulnerable to cracking mechanisms (e.g. Chloride Stress Corrosion Cracking (SCC), Sulphide Stress Cracking (SSC)). In some cases it may be preferable to have a corrosion mechanism where the metal loss can be safely monitored with inspection versus a cracking mechanism which can occur suddenly and without any warning.

Other considerations when considering CRA’s are:

1.

Cost: CRA’s are more expensive than carbon steels and so this needs to be factored into the economics of a project. This is known as “whole life costing” and includes procurement, construction, operation, and decommissioning costs. Typically, CRA’s become more attractive as the required lifetime of a project increases.

2.

Welding: CRA’s require extra care when welding compared to carbon steels which adds to the cost of construction. It also requires welders who are more highly qualified and so another consideration is, will these welders and quality control personnel be available locally at the project site. This is often related to where in the world the project is located.

3.

Galvanic Corrosion: Since CRA’s are more resistant to corrosion than carbon steel, problems can occur when they are joined to carbon steel or other more corrosive materials. The CRA can act as a cathode which promotes corrosion of the other metal. Incorrectly specified weld material is especially vulnerable to this, resulting in Preferential Weld Corrosion.

4.

Construction & Commissioning: If a CRA is selected to resist a specific operational corrosion threat, such as CO2 corrosion, it is important to ensure that during the construction and commissioning phase it does not come into contact with a fluid that is corrosive to it. There are many examples where this has occurred. Probably the most well-known examples are where a stainless steel has been chosen for a pipeline for its CO2 resistance but during commissioning it has been hydrotested with poor quality water which contains chlorides and oxygen (and often bacteria) causing the stainless steel to corrode and/or crack before it ever enters operational service.

5.

Availability: Due to manufacturing challenges and mill constraints, CRAs may not be readily available, and often have a long lead time.

Having considered all these factors let’s now return to the original question of when to use CRA’s in upstream production. Before considering CRA’s, it is usual to evaluate carbon steel as a base case for construction. Once this has been done CRA’s can be evaluated and compared to the carbon steel base case. Key considerations on top of design factors including mechanical properties, are:

1.

Risk: CRA’s are often selected when the risk of premature failure of equipment made from carbon steel is unacceptable. If a project is expected to last 25 years but the mitigated corrosion rate of carbon steel will render the equipment unusable before that, then a CRA is likely to be a good option. Some engineers would like to be able to use a maximum, uninhibited corrosion rate for carbon steel as the trigger for moving to CRA’s, e.g. 3 mm/y. Whilst this provides a simple approach it is not the corrosion rate that is key – it is the time to failure that is important. Note that failure is not the point at which the equipment perforates and leaks ( often known as a loss of primary containment – LOPC), but the point at which it no longer meets the pressure requirements of the equipment. There are well known operations that have uninhibited corrosion rates of >5mm/y that are constructed from carbon steel in which corrosion is successfully mitigated to 0.1 mm/y

or lower.

2.

Operability: This is related to the risk section above but is worth noting separately. In many cases upstream equipment can be constructed from carbon steel and both internal and external corrosion successfully controlled using a combination of chemical inhibition, coatings, and/or cathodic protection. However, these mitigation systems are known as “active” mitigation and require monitoring, maintenance and repairs to be undertaken during the life of the operation. These require appropriately qualified personnel which incur operational costs. Moreover in remote land-based locations the facilities can be spread over very large areas, requiring staff and equipment to be driven for many hours – often called “windshield time” which is unproductive time and has associated safety risks. In such cases it may be more appropriate to select a CRA which would significantly reduce many of these activities and reduce the total risk of an operation. Similar arguments apply to subsea operations which are difficult and costly to access. Today, many subsea facilities are built entirely out of CRA’s for this reason.

3.

Cost: This was discussed previously and is a key factor in deciding between carbon steel and CRA materials. The M&C engineer will need to look at the whole life costing of both options, which will then be assessed by the project commercial team, who will make a decision based on all project risks

and costs.

In summary, hopefully it is clear that there are many factors to consider when selecting a CRA for upstream equipment. Sometimes the decision to use a CRA can be simple and examples of this include:

1. When corrosion rates of carbon steel are unacceptably high.

2. When the construction and operational costs for managing a carbon steel facility exceed the cost of using CRA for the project.

3. When the risk of maintaining an active mitigation system for carbon steel equipment is unacceptable.

4. And finally, when a combination of very high strength and corrosion resistance are essential.

However, it is far more common that the decision is not simple and it is the role of the M&C engineer to consider the risks and costs of both carbon steel and CRA options for a project. It is also usual that a single engineer will not have all the skills necessary to make this decision and will call on colleagues with specialised knowledge of materials and corrosion to support the evaluation.

Further Reading

There are many excellent sources for further information on CRA’s – some good starting points are:

1.

https://nickelinstitute.org/media/1663corrosionresistantalloysintheoilandgasindustr

2.

Bijan Kermani, Fellows Corner, Corrosion Management, Issue 165, Institute of Corrosion Magazine, January/February 2022, page 19.

3.

B. Kermani and D. Harrop, “Corrosion and Materials in Hydrocarbon Production”, published by John Wiley & Sons td, 2019. (note this book is an excellent reference and covers all aspects of upstream corrosion and materials topics).

Bill Hedges, Past President ICorr

YEP

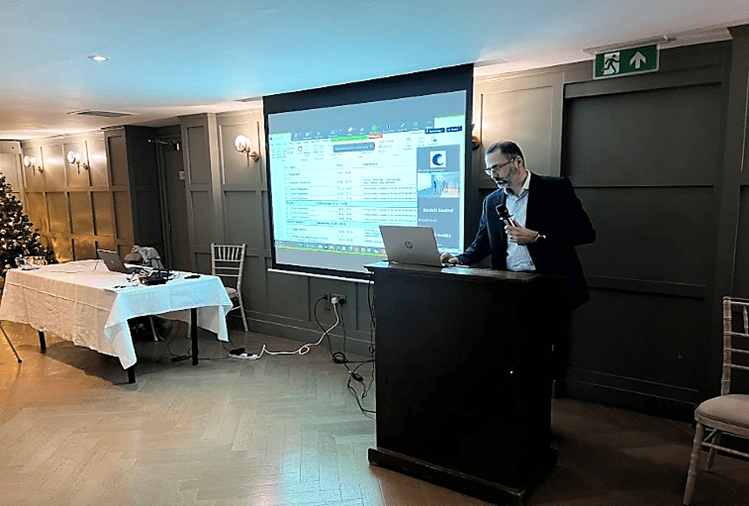

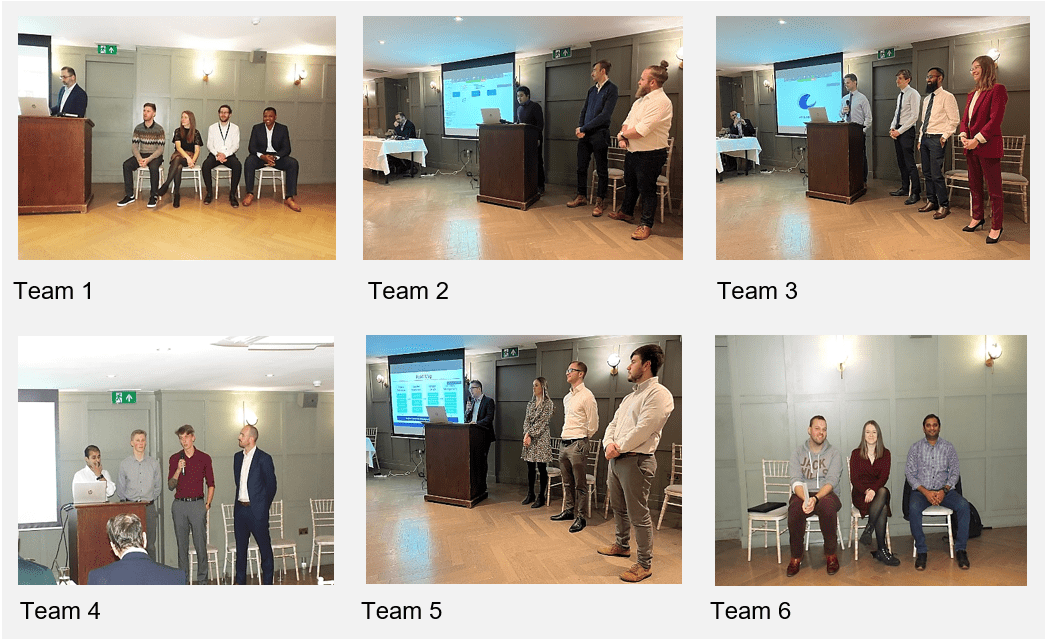

The Aberdeen Branch hosted the Young Engineer Programme (YEP) 2022 final on 24th November ’22, at the Palm Court Hotel, which was attended by over 40 in person, plus around 15 attendees online.

It was more than 18 months ago that the branch first considered hosting this event in Scotland, after 3 very successful events hosted by London Branch. David Mobbs, Trevor Osborne, and Danny Burkle, all very kindly supported the branch in the early days of YEP 2022.

The Young Engineer’s Programme was conceived some 10 years previously by the ICorr London Branch and has been generously sponsored since then by BP with the following in mind, perceived skill shortages in the industry, preparing graduates for entry into the industry with an enhanced skillset, and to be the first stage in achieving MICorr / CEng.

The ICorr YEP remains extremely popular with our younger and aspiring corrosion engineers, and this 4th YEP had 24 candidates, selected from over 50 applicants The Institute is very grateful to the Aberdeen committee who worked hard, especially Hooman Takhtechian (2021-2022 session chair) and Steve Paterson (YEP mentor supervisor / Case study organiser), superbly supported on the night and throughout the YEP by, Muhammad Ejaz / Adesiji Anjorin, the current branch chair and vice chair respectively.

YEP 2022 Co-ordinator, Hooman Takhtechian

This year’s selection criteria were:

- Early stage of their career related to corrosion.

- 2 to 6 years relevant experience.

- 35 and under.

- Relevant academic background.

- Based in Aberdeen, or willing to travel at their own cost.

The YEP committee had great difficulty in selecting those to go forward. The case study teams were based on their experience, academic background, and employer, to ensure not being in the same company as the other team members or the mentor, with the average experience for each team being 4 to 4.5 years.

| Name |

Surname |

Company / University |

Team |

| Stephanie |

Breen |

Kent Plc |

1 |

| Ross |

Burgoyne |

Stork |

1 |

| Stuart |

Clark |

Codex |

1 |

| Austin |

Mwana |

Oceaneering International |

1 |

| Name |

Surname |

Company / University |

Team |

| Natasha |

Andean |

PMAC Group |

2 |

| Christopher |

Hynes |

IMRANDD |

2 |

| Lewis |

Shand |

Stork |

2 |

| Badriz |

Talhah |

Oceaneering International (now Aker Solutions) |

2 |

| Name |

Surname |

Company / University |

Team |

| Matthew |

Drummond |

PIM |

3 |

| Olesia |

Gautsel |

TechnipFMC |

3 |

| Vinooth |

Rajendran |

Robert Gordon University |

3 |

| Cameron |

West |

Kent Plc |

3 |

| Name |

Surname |

Company / University |

Team |

| Mohammed Mustak |

Ahmed |

Intertek |

4 |

| Ross |

Devaney |

Glacier Energy |

4 |

| Kerrin |

Graham |

Kent Plc |

4 |

| Joshua |

Thornton |

PIM |

4 |

| Name |

Surname |

Company / University |

Team |

| Rosie |

Bird |

PIM |

5 |

| Jamie |

Hillier |

Xodus |

5 |

| Lee |

Hunter |

PBS Offshore |

5 |

| Christopher |

Slater |

Stork |

5 |

| Name |

Surname |

Company / University |

Team |

| Craig |

Cunningham |

Stork |

6 |

| Shravan |

Khairy |

National Physical Laboratory |

6 |

| Eilidh |

MacDonald |

Subsea 7 |

6 |

| Lewis |

Mann |

TechnipFMC |

6 |

YEP 2022 Participants

The 2022 case study exercise was complex, and focused on good corrosion management approaches under difficult conditions, requiring careful consideration of:

- A 15year old offshore platform in sweet service.

- Poor corrosion management to date.

- Possible new owner with another 10 years’ service.

- Possible tie-in of new field with slightly sour fluids.

- Dealing with an intermediary integrity services contractor.

- Difficult and demanding client.

- Subsidiary of international operator.

- Based on an actual platform in the North Sea.

- High level assessment (and ranking) of threats.

- Mitigation measures – corrosion management system.

- Material options for required new pipeline.

- The management and impact of change in operations (MOC).

- Identifying all other relevant factors in dealing with client.

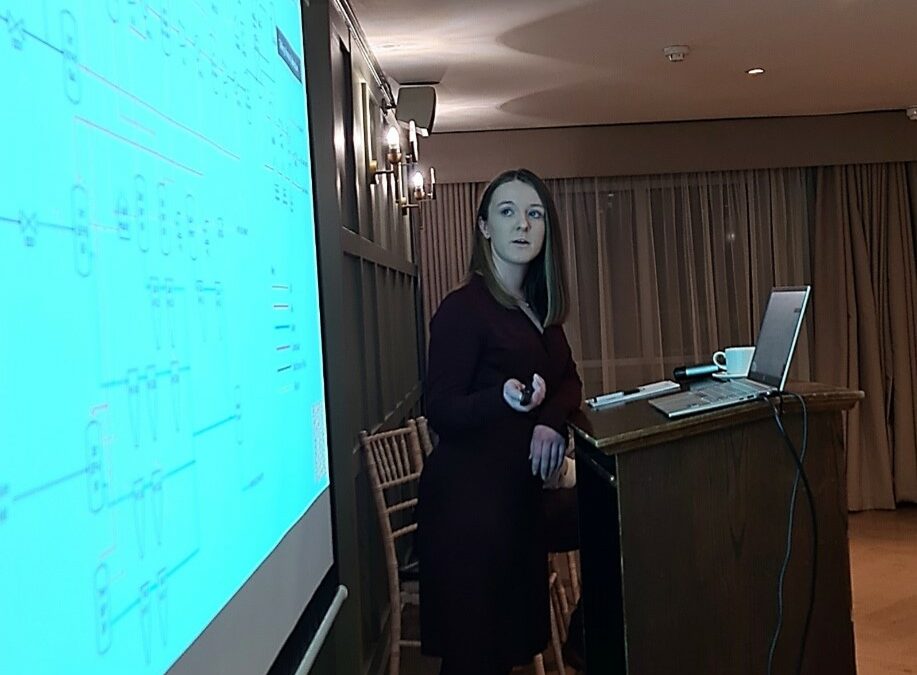

YEP 2022 case study lead, and the ICorr CED All Energy chair, Steve Paterson, explains proceedings

Some key aspects of the exercise were to:

- Analyse and discuss the information and data provided.

- Identify any gaps in information and any assumptions that may need to be made.

- Perform a high-level risk assessment to identify key threats to the mechanical integrity of the pressurised systems (structural integrity was excluded).

- Identify what further information or data required for the other tasks in the exercise.

- Propose a systematic approach to manage the key threats including mitigation measures, corrosion control requirements, performance monitoring, and the resources required to manage the process.

- Propose materials of construction for a pipeline, including welding consumables, and any testing requirements to tie-back the new reservoir to the platform, and explain the basis for the materials selection and how any corrosion threats will be mitigated.

- Identify what changes, if any, to the existing facilities would be required should the new sour reservoir be tied-back to the

- Propose a strategy for convincing Capercaillie Energy (the integrity management contractor) that your approach is the optimal solution and that you are the right team to do the job.

The marking criteria for the YEP case study presentation were:

- Analysis of the scenario and current integrity status of the pressurised systems of the platform (20 marks).

- Application of a systematic methodology to manage corrosion and surveillance activities (20 marks).

- Viability of the proposed approach to prolong service life (10 marks).

- Assessment of material options for the new pipeline (10 marks).

- Assessment of the impact of change in operation with H2S (10 marks).

- Identification and assessment of factors in dealing with the client (10 marks).

- Overall quality and balance of the presentation, plus team coordination as demonstrated by the presentation (20 marks).

Only 20mins were allowed per team for their presentation, with strict penalties being applied for those going over.

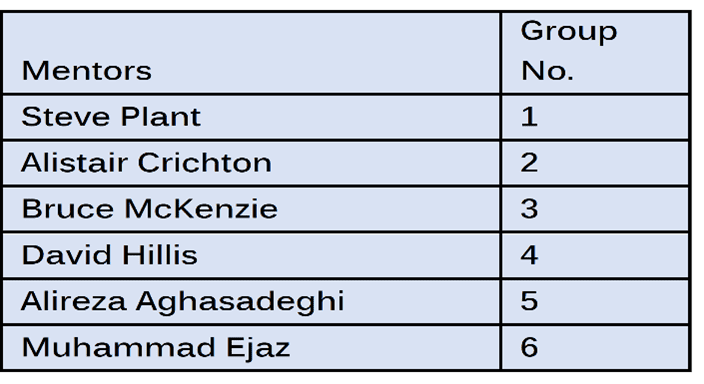

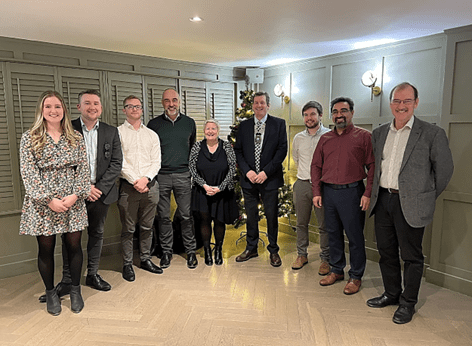

Contestants, mentors, judges and ABZ committee members on the night

The Aberdeen committee would like to offer its special thanks to all of the following lecturers, mentors, and judges.

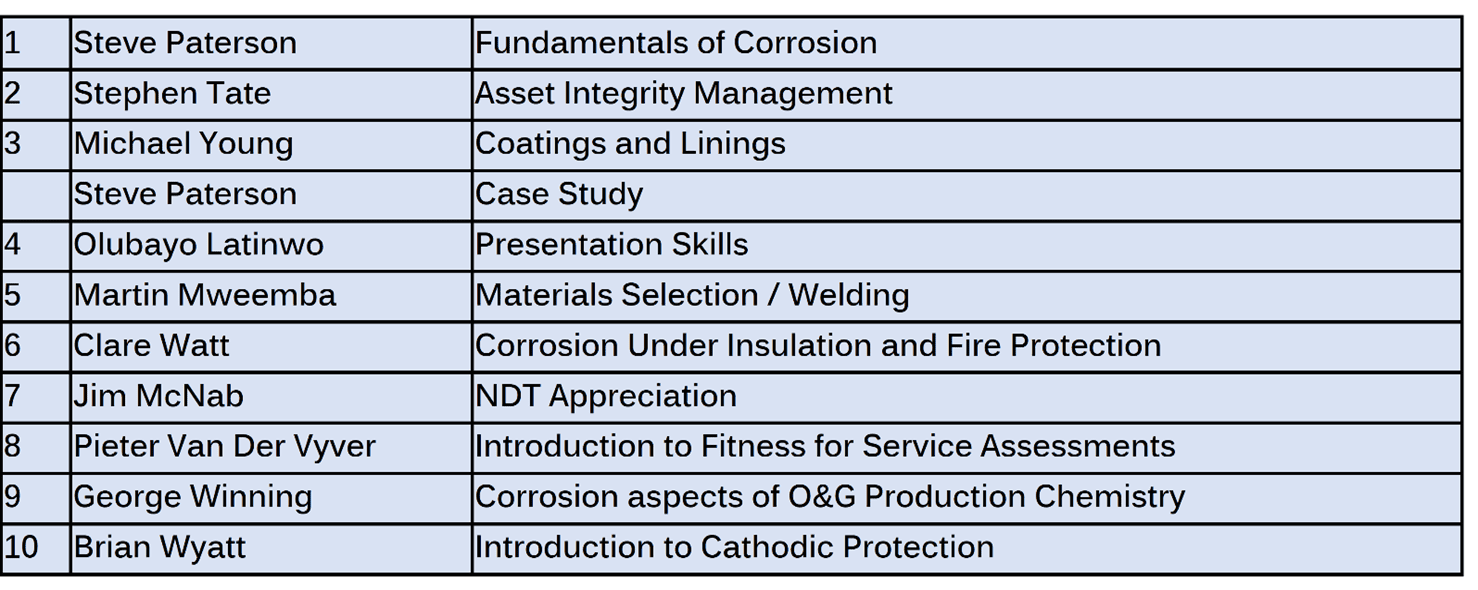

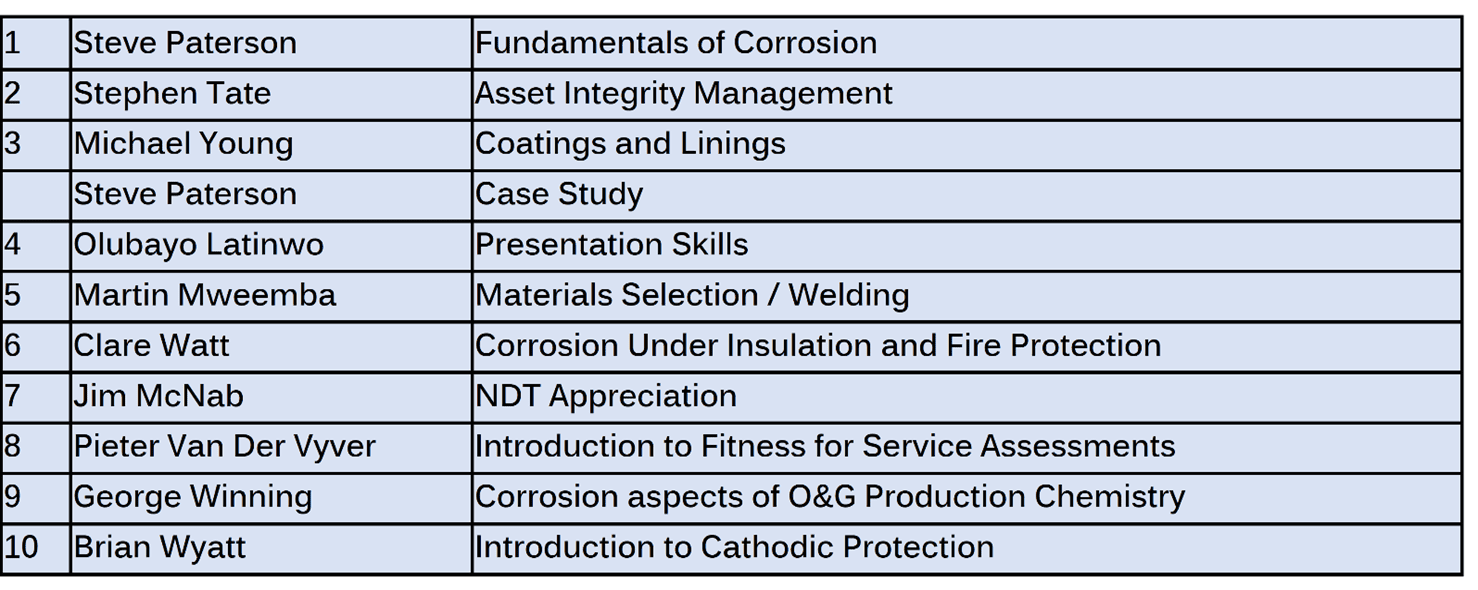

YEP 2022 course lecturers

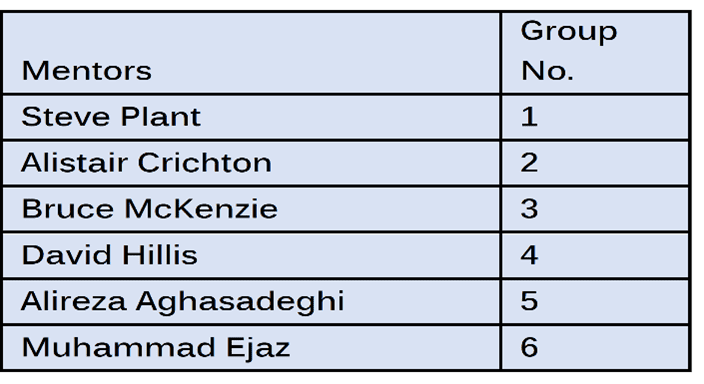

The YEP course mentors were:

The judges on the night were:

- Chris Williams, (BP Sunbury – Key Sponsor).

- Susan Cushnaghan, (formerly of Shell Aberdeen).

- Stephen Tate (2022-2024 ICorr President).

Judges ready to Announce Winners

All the participating teams engaged fully with the brief and gave a tremendous series of presentations providing many different solutions to the task in hand including net zero considerations, their enthusiasm was a joy to watch.

Unfortunately, Teams 2 and 6 were missing colleagues on the night due to illness but they still performed brilliantly.

It was a very hard decision for the judges, but in the end Team 5 stood out as the best all-rounders and enactors of the task in hand. The Institute offers their warmest congratulations to all the Team 5 members, as they head off to AMPP Annual Conference & Expo 2023 19-23 March, all expenses paid courtesy of Key sponsor BP.

The YEP 2022 winning team 5, Judges, President and team 5 mentor. From left to right, Rosie Bird, Lee Hunter, Jamie Hillier, Chris Williams (Judge), Susan Cushnaghan (Judge), Stephen Tate (Judge), Christopher Slater, Alireza Aghasadeghi (mentor), and Steve Paterson (Case study lead)

Winner of the Leadership Prize

After receiving feedback from all the mentors, judges and committee members, based on the performance during the whole programme, teamwork and presentation skills on the competition evening, Eilidh Macdonald was selected as the outstanding YEP 2022 individual participant. The Institute also offers their congratulations to Eilidh on receiving this recognition, who will also be eligible to attend the AMPP leadership course, all expenses paid. This is very well deserved.

Eilidh MacDonald, Winner of the Leadership Prize from Team 6

YEP 2024

The Institute are already planning for YEP 2024, which will be managed by the Young ICorr Division.

Details will be announced later during 2023, however interested parties can register their advance interest to the new YICorr chair, James McGladdery, James.McGladdery@uknnl.com

Industry News

The following documents have obtained substantial support

during the past two months, and have been submitted to the ISO member bodies for voting, or formal approval.

ISO/FDIS 1518-1 Paints and varnishes — Determination of scratch resistance — Part 1: Constant-loading method (Revision of 2019 standard)

ISO/DIS 3882 Metallic and other inorganic coatings — Review of methods of measurement of thickness (Revision of ISO 2003 standard)

ISO/FDIS 4212 Corrosion of Metals and Alloys— Method of oxalic acid etching test for intergranular corrosion of austenitic stainless steel

ISO/DIS 19735 Corrosion of metals and alloys — Corrosivity of atmospheres —Mapping areas of increased risk of corrosion

New International standards published in the past two months.

ISO 1522:2022 Paints and varnishes — Pendulum damping test

ISO 3079:2022 Two-electrode method using acetic acid to measure pitting potential of aluminium and aluminium alloys in chloride solutions

ISO 4628-5:2022 Paints and varnishes — Evaluation of quantity and size of defects, and of intensity of uniform changes in appearance — Part 5: Assessment of degree of flaking

ISO 9227:2022 Corrosion tests in artificial atmospheres— Salt spray tests

ISO 10062:2022 Corrosion tests in artificial atmosphere at very low concentrations of polluting gas(es)

ISO 11127-7:2022 Preparation of steel substrates before application of paints and related products — Test methods for non-metallic blast-cleaning abrasives — Part 7: Determination of water-soluble chlorides

ISO 23669:2022 Corrosion of metals and alloys — Requirements for localised corrosion and environmentally assisted cracking testing of additively manufactured metals and alloys

ISO 24239:2022 Corrosion control engineering life cycle in fossil fuel power plants — General requirements

Corrosion Control, Fellows Corner

Telling the Truth and Nothing But the Truth

Peter Elliott, Corrosion & Materials Consultancy, Inc., Las Vegas, USA.

This is the first in an occasional column, to inspire new graduates into working within our industry, by highlighting the interesting and varied aspects of a career in corrosion control, as experienced by members of the institute.

Times change, as does the understanding of corrosion and its control. As a graduating metallurgist with interests in high temperature oxidation and corrosion, my first research job, with Imperial Metal Industries, Birmingham, was the challenge of developing a metal, actually a refractory metal alloy containing tantalum, hafnium and niobium, that could survive a round trip into space. Using a high-temperature glaze from the Potteries as a coating – it worked. My interests were further enhanced by attendance at a local Institute branch meeting on corrosion by Professor T.K. (Ken) Ross, a chemical engineer, who enticed me to leave the space race and join him at what was then the University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology (UMIST). He invited me to conduct research and asked if I knew anything about boilers. To my surprise, when I replied “no”, he replied “Perfect, I want someone with an open mind. Come and join us. When can you start?”

The return to my hometown of Manchester, to a Chemical Engineering Department, which in 1968, witnessed the creation of the Corrosion and Protection Centre – the first such academic department in the world to focus on teaching, research and industrial consulting services addressing corrosion and its control. Joining the UMIST staff my interest in boilers grew, but, by noting that metals don’t always stay hot, so did my knowledge in aqueous corrosion,including the measurement of atmospheric corrosion, which was particularly valuable – see below.

For countless years perceptions about corrosion have suggested that this often visually alarming disease is unsurmountable. Corrosion cost surveys proclaimed enormous financial losses, classed as high percentages of the Gross National (or Gross Domestic) Profit.[1] Akin to cancer and other diseases, there are parallels with corrosion control, where advances in monitoring, understanding, and treating causes with palliative cures, has grown significantly. Over the years I have noted parallels to the UK National Health Service that operates more as a National Disease Service, where exercise and healthy foods were lacking, medicines were not taken, examinations were not performed, and surgery or continued hospitalisation was required. A better understanding of corrosion, promulgated by professional societies, at least recognising (better still understanding), the interplay of thermodynamics [can a material react?] and kinetics [how fast can it be ?]. Those who seek young, experienced chemists, engineers, and metallurgists, are apparently ignorant to this oxymoron; age hardening (misquoted) reflects years of experience along with expertise.

I have continued my interest in corrosion failures – from establishing a museum in what was the UMIST Corrosion & Protection Centre so many years ago, to sharing examples at countlessmeetings and in publications.[2] I am particularly fascinated by unusual cases, for example a case that revealed a “crack” is not a crack, which brings

back memories of Turner’s Laws of Corrosion, e.g., “Nor all

that be cracked, needeth it be SCC”.[3]

The case in question pertains to a leak in the top of a ¾”- diameter domestic cold-water pipe, which after 21 years’ service, was first attributed to a lateral crack (Figure 1A), until laboratory examination showed a complex pattern of localised pitting from the inside of the pipe (Figure 1B). The cause was apparent when the farmhouse homeowner shared the history of his convenient (for him) but unusual water sources, comprising of two years “dirty” well water, followed by 20 years of soft rainwater collected from the roof of his building. These uniquely different conditions favoured localised pitting, which progressed with sustained attack from the soft water that ultimately fully penetrated through the top of the copper pipe as the pinhole leak. The copper was not defective; there was no evidence of stress corrosion cracking.

To date, with over two million airline miles and many thousand traveled by road, my response to the question “what have you learned most?” is my knowledge of geography! In a recent litigation matter an opposing expert stated that my report was biased. A few months later – when monitored atmospheric data was available – truth prevailed. The settlement was enhanced as the bias was refuted. Telling the truth is the key to corrosion control.

References

1. Hoar report (UK), NIST, Library of Congress (USA)

2 P. Elliott, Gallery of Corrosion Damage”, Metals Handbook, 13B, ASM International, p.629-646, 2005.

3 M. E. D. Turner (Mervyn) – deceased – private communication.

Fig 1A “Crack” in top of ¾”diameter copper pipe.

Detail of “crack.”

OD top pf pipe.

Close to “crack” location.