Understanding the Impact of Microbial Activity on Corrosion

Corrosion represents a formidable challenge to almost every industry. It affects infrastructure integrity and operational performance. The degradation of metal structures, primarily due to electrochemical reactions, poses significant economic burdens and safety risks. Consequently, effective corrosion management is critical to prolong the lifespan of industrial structures and infrastructures, and to ensure safety and uninterrupted production.

Microbial metabolic activity has come into focus due to its profound acceleration of corrosion. With the significant improvement of our understanding of industrial microbiology, and the number of MIC failures with massive financial, operational, and health and safety consequences, it is critical that professionals acquire pertinent competencies to develop robust prevention and control strategies.

In this article, we look at a few basics behind the science, and how you can improve your own knowledge to both protect company assets and advance your career.

Microbial Influences on Corrosion

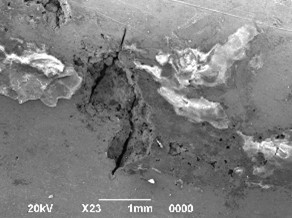

Microbiologically influenced corrosion (MIC) occurs through complex mechanisms. These involve the formation of biofilms and the production of corrosive metabolites on a metal surface, leading to an accelerated and localised form of corrosion. They can colonise a system with just traces of water. Microbes are symbiotic and work in a cyclic mode with detrimental effect. Accelerated Low Water Corrosion (ALWC) is a special case of MIC affecting steel piles (e.g. in ports) and commonly involves the effect of one or collective groups of cycling microorganisms including sulphur reducing/oxidising bacteria and iron reducing/oxidising bacteria, resulting in severe damage.

The detrimental impact of uncontrolled microbial activities in industrial systems extend beyond the acceleration of corrosion. Uninhibited microbes could have a detrimental effect on cement and polymeric structures, processing systems such as water filtration, plugging of reservoir formation, and souring.

The detrimental impact of uncontrolled microbial activities in industrial systems extend beyond the acceleration of corrosion. Uninhibited microbes could have a detrimental effect on cement and polymeric structures, processing systems such as water filtration, plugging of reservoir formation, and souring.

There are many types of corrosive microorganisms including sulphate-reducing prokaryotes (SRP), acid-producing bacteria (APB), iron-oxidising/reducing bacteria (IOB and IRB), and denitrifying bacteria (DNB). These microbes thrive in diverse environmental conditions and are the prime cause of a number of premature failures in different industries. MIC is predominately manifested in the form of pitting.

· Sulphate-Reducing Prokaryotes (SRP)

Sulphate-reducing prokaryotes (SRP) consist of both bacteria (SRB) and archaea (SRA). They are obligate anaerobes and respire sulphate to produce hydrogen sulphide (H₂S). This wide group of prokaryotes are prevalent in most industries.

Sulphide generated by SRP reacts with iron to form the strong cathodic iron sulphide (FeS) to steel leading to pitting, and posing significant risks to system integrity and equipment.

· Acid-Producing Bacteria (APB)

· Acid-Producing Bacteria (APB)

Acid-producing bacteria generate organic acids as metabolic byproducts. They thrive in both aerobic and anaerobic (facultative) conditions. APB affect corrosion through two different mechanisms:

- Generated acids significantly lower pH levels at the metal surface, creating highly corrosive environments.

- Generated organic acids are used by other co-existing groups of detrimental microbes as a carbon source (symbiotic effect) to support reproduction and metabolic activities.

· Iron-Oxidising/Reducing Bacteria (IOB and IRB)

Iron-oxidising bacteria (IOB) are aerobic microorganisms that derive energy from the oxidation of ferrous to ferric iron. These bacteria are often found in toxic environments and abundant iron. Iron reducing bacteria (IRB) are facultative and they reduce ferric iron to soluble ferrous iron.

The cyclic mode of IOB and IRB destabilises the oxide layer leading to accelerated localised corrosion. This type of corrosion is particularly insidious, as it can occur beneath seemingly protective corrosion products.

· Denitrifying Bacteria (DNB)

· Denitrifying Bacteria (DNB)

Denitrifying bacteria (DNB) are a large group of facultative microorganisms. They reduce nitrogenous compounds to nitrogen with the possibility of intermittent production of nitrite and ammonia. Nitrite, under certain conditions, increases the risk of pitting while ammonia poses a major risk to copper alloys.

Detection and Monitoring of Microbial Corrosion

Managing MIC presents unique challenges, which fall into five distinct categories:

- Company to recognise MIC in internal documentation including standards, guidelines, regulations, best practices, and professional codes.

- MIC to be considered at the design stage with the implementation of adequate barriers from the start of operation.

- Include MIC as an element of the company corrosion management system including risk assessment.

- Active collaboration between corrosion engineers and microbiologists to ensure a system-specific monitoring system is in place, and to establish a database of all corrosion cases that may involve microbes.

- A pro-active management with an alive performance improvement steps and cycle system for prevention and adjustment to any potential changes.

Regular and consistent sampling procedures are critical for managing MIC. Techniques such as swabbing, scraping, and fluid collection are employed to collect samples to ensure a better understanding of operating conditions. Analytical techniques include microbiological culturing, molecular microbiology techniques like polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and geochemical and nutritional analyses.

Regular and consistent sampling procedures are critical for managing MIC. Techniques such as swabbing, scraping, and fluid collection are employed to collect samples to ensure a better understanding of operating conditions. Analytical techniques include microbiological culturing, molecular microbiology techniques like polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and geochemical and nutritional analyses.

Preventing and Controlling MIC

MIC control and prevention techniques can be broadly divided into two categories:

- System resistivity to microbial colonisation; and

- Methodologies to kill or control system microbes.

· Material Selection and Coatings

Choosing fit-for-purpose corrosion-resistant materials and applying protective coatings are effective strategies for preventing microbial corrosion. Another example is the selection of specialised alloys that are resistant to microbial activities but do not affect colonising colonies. Note, coatings may not affect microbial activities, but they create a barrier between microbes and metal.

· Environmental Control

Controlling environmental factors such as flow rate, oxygen concentration, temperature, precipitation, separation, stagnation, and nutritional availability can mitigate microbial growth.

· Cathodic Protection (CP)

Raising the applied potential by -100mV (in the negative direction) can prevent microbes from attaching to a metal surface. Cathodic protection does not affect microbial activities, but it prevents their attachment to a metal surface due to the generation of hydroxyl radicals.

· Biocides

Biocides are chemical agents designed to kill or inhibit microbial growth. Commonly used organic biocides include glutaraldehyde, quaternary ammonium compounds, and THPS. Biocide treatment is system-specific and should be regularly reviewed and upgraded every a few years. Disinfectants such as chlorine, chlorine dioxide, ozone and hydrogen peroxide are commonly used in water treatment.

· Use of Bacteriophages

Bacteriophages are viruses that infect and kill specific bacteria. They offer a targeted treatment to controlling microbial populations. Phage therapy is an emerging technique with potential for precise microbial management without the drawbacks of biocides.

· Competitive Exclusion Strategies

· Competitive Exclusion Strategies

Competitive exclusion (survival of the fittest) involves the addition of a practical and economical substrate to stimulate the activities of ‘friendly’ microbes to control detrimental bacteria. This strategy leverages natural microbial interactions to maintain a balanced and less corrosive environment.

· Mechanical Cleanliness

Keeping equipment clean and free of deposits and debris helps to minimise problems related to MIC. For pipelines, pigging is an effective way for penetrating and damaging sessile colonies. The technique is most effective against bacteria when combined with a high concentration of biocide.

MIC Training and Case Studies

Recognising the need to address the challenges of managing MIC, the Institute of Corrosion offers two tailored courses designed to aid consultants and corrosion professionals in this field: the one-day Awareness Course and the comprehensive four-day Certified MIC Technologist Course.

The Awareness Course provides an overview of MIC phenomenon, while the MIC Technologist Course offers in-depth training, including practical sessions. An optional exam for the Certified MIC Technologist Course enhances professional credentials. The courses are available at ICorr Headquarters or your own company premises, and use a number of case studies to share industry best practices.

The courses benefit managers, project leaders, industrial biologists, engineers, scientists, industrialists and technical staff, in different industries including oil and gas, marine, water, infrastructure, and power generation sectors.

Enrolling in these courses equips professionals with the knowledge to monitor and mitigate MIC and safeguarding assets, and reduce costs, while fostering career growth and networking within the wider corrosion community.

For more information about our upcoming MIC Training Courses, please contact the Institute of Corrosion by email (admin@icorr.org) or phone on +44 (0) 1604 438 222.

This doesn’t sound complete but there are a number of ways it could be edited – please can you review?