Ask the Expert

Question:

When should you use corrosion resistant alloys in upstream production? CM

Answer:

This is a wonderfully simple question that does not have a simple answer. Corrosion Resistant Alloys can be an excellent material choice for combatting corrosion and they are an important addition to the options that we have as Materials and Corrosion (M&C) professionals. However, as with all materials there are pros and cons and it is the role of M&C engineers to evaluate the best option.

It is important that we recognise that when we talk about a Corrosion Resistant Alloy (CRA) we are referring to a specific metal or alloy that is resistant to a specific corrosion mechanism or mechanisms. For example, in Upstream operations, for some applications,316L stainless steel is increasingly used for its resistance to carbon dioxide (CO2) corrosion, and can be considered a CRA for this threat. However, this alloy is vulnerable to corrosion in oxygenated sea water and so is not a good material for this environment. So before selecting a corrosion resistant material, in additional to many other parameters, it is very important we define the corrosion mechanism or mechanisms that it needs to resist – on both the internal and external surfaces of the equipment.As in the example above many CRA’s are stainless steels, and historically the term “stainless steel” was used generically to indicate corrosion resistant metals. The term CRA emerged when alloys that do not have iron (Fe) as their majority element started to be used, e.g. nickel and titanium based alloys.

For our colleagues who are not M&C engineers, the term CRA can be misleading because there is no metal or alloy that is immune to every corrosion environment. To make this point I have sometimes joked that CRA should mean “Can Rust Actually”. A key role of M&C engineers is to educate colleagues on the limits of CRA’s in particular environments.

A further consideration when selecting a CRA is that we do not eliminate one corrosion mechanism only for it to be replaced by another. For example many stainless steels are resistant to CO2 corrosion but vulnerable to cracking mechanisms (e.g. Chloride Stress Corrosion Cracking (SCC), Sulphide Stress Cracking (SSC)). In some cases it may be preferable to have a corrosion mechanism where the metal loss can be safely monitored with inspection versus a cracking mechanism which can occur suddenly and without any warning.

Other considerations when considering CRA’s are:

1.

Cost: CRA’s are more expensive than carbon steels and so this needs to be factored into the economics of a project. This is known as “whole life costing” and includes procurement, construction, operation, and decommissioning costs. Typically, CRA’s become more attractive as the required lifetime of a project increases.

2.

Welding: CRA’s require extra care when welding compared to carbon steels which adds to the cost of construction. It also requires welders who are more highly qualified and so another consideration is, will these welders and quality control personnel be available locally at the project site. This is often related to where in the world the project is located.

3.

Galvanic Corrosion: Since CRA’s are more resistant to corrosion than carbon steel, problems can occur when they are joined to carbon steel or other more corrosive materials. The CRA can act as a cathode which promotes corrosion of the other metal. Incorrectly specified weld material is especially vulnerable to this, resulting in Preferential Weld Corrosion.

4.

Construction & Commissioning: If a CRA is selected to resist a specific operational corrosion threat, such as CO2 corrosion, it is important to ensure that during the construction and commissioning phase it does not come into contact with a fluid that is corrosive to it. There are many examples where this has occurred. Probably the most well-known examples are where a stainless steel has been chosen for a pipeline for its CO2 resistance but during commissioning it has been hydrotested with poor quality water which contains chlorides and oxygen (and often bacteria) causing the stainless steel to corrode and/or crack before it ever enters operational service.

5.

Availability: Due to manufacturing challenges and mill constraints, CRAs may not be readily available, and often have a long lead time.

Having considered all these factors let’s now return to the original question of when to use CRA’s in upstream production. Before considering CRA’s, it is usual to evaluate carbon steel as a base case for construction. Once this has been done CRA’s can be evaluated and compared to the carbon steel base case. Key considerations on top of design factors including mechanical properties, are:

1.

Risk: CRA’s are often selected when the risk of premature failure of equipment made from carbon steel is unacceptable. If a project is expected to last 25 years but the mitigated corrosion rate of carbon steel will render the equipment unusable before that, then a CRA is likely to be a good option. Some engineers would like to be able to use a maximum, uninhibited corrosion rate for carbon steel as the trigger for moving to CRA’s, e.g. 3 mm/y. Whilst this provides a simple approach it is not the corrosion rate that is key – it is the time to failure that is important. Note that failure is not the point at which the equipment perforates and leaks ( often known as a loss of primary containment – LOPC), but the point at which it no longer meets the pressure requirements of the equipment. There are well known operations that have uninhibited corrosion rates of >5mm/y that are constructed from carbon steel in which corrosion is successfully mitigated to 0.1 mm/y

or lower.

2.

Operability: This is related to the risk section above but is worth noting separately. In many cases upstream equipment can be constructed from carbon steel and both internal and external corrosion successfully controlled using a combination of chemical inhibition, coatings, and/or cathodic protection. However, these mitigation systems are known as “active” mitigation and require monitoring, maintenance and repairs to be undertaken during the life of the operation. These require appropriately qualified personnel which incur operational costs. Moreover in remote land-based locations the facilities can be spread over very large areas, requiring staff and equipment to be driven for many hours – often called “windshield time” which is unproductive time and has associated safety risks. In such cases it may be more appropriate to select a CRA which would significantly reduce many of these activities and reduce the total risk of an operation. Similar arguments apply to subsea operations which are difficult and costly to access. Today, many subsea facilities are built entirely out of CRA’s for this reason.

3.

Cost: This was discussed previously and is a key factor in deciding between carbon steel and CRA materials. The M&C engineer will need to look at the whole life costing of both options, which will then be assessed by the project commercial team, who will make a decision based on all project risks

and costs.

In summary, hopefully it is clear that there are many factors to consider when selecting a CRA for upstream equipment. Sometimes the decision to use a CRA can be simple and examples of this include:

1. When corrosion rates of carbon steel are unacceptably high.

2. When the construction and operational costs for managing a carbon steel facility exceed the cost of using CRA for the project.

3. When the risk of maintaining an active mitigation system for carbon steel equipment is unacceptable.

4. And finally, when a combination of very high strength and corrosion resistance are essential.

However, it is far more common that the decision is not simple and it is the role of the M&C engineer to consider the risks and costs of both carbon steel and CRA options for a project. It is also usual that a single engineer will not have all the skills necessary to make this decision and will call on colleagues with specialised knowledge of materials and corrosion to support the evaluation.

Further Reading

There are many excellent sources for further information on CRA’s – some good starting points are:

1.

https://nickelinstitute.org/media/1663corrosionresistantalloysintheoilandgasindustr

2.

Bijan Kermani, Fellows Corner, Corrosion Management, Issue 165, Institute of Corrosion Magazine, January/February 2022, page 19.

3.

B. Kermani and D. Harrop, “Corrosion and Materials in Hydrocarbon Production”, published by John Wiley & Sons td, 2019. (note this book is an excellent reference and covers all aspects of upstream corrosion and materials topics).

Bill Hedges, Past President ICorr

Ask the Expert

The questions in this issue feature insulated stainless steel pipework, and transporting CO2

Question:

Should 304 stainless steel pipework be coated prior to insulation? CM

Answer:

Corrosion under insulation in austenitic stainless steel manifests itself in the form of chloride-induced stress corrosion cracking (CISCC), also referred to as external stress corrosion cracking (ESCC), as the source of chlorides is external to the process environment.

The mechanism of stress corrosion cracking (SCC) is well known in industry and can be found in lots of publications which are in the public domain. The mode of cracking failure is typically trans granular. There are a number of conditions that are in play when it comes SCC, as detailed below:

1. A susceptible 300 series austenitic stainless steel, in this case 304

2. Residual or applied surface tensile stresses

3. The presence of halides from either the environment of the insulation itself

4. Process temperatures leading to metal temperature in the range 50° to 150°C

5. An electrolyte (water)

All of the above are ever present, and hence the need to use specific coatings on stainless steel. The types of coating that can be employed are varied depending on the operating temperature, typically:

• Organic epoxy chemistry is capable of resisting cryogenic temperatures and up to 120/150C, depending on formula

• Epoxy phenolics/novolacs are suitable from cryogenic temperatures and up to 200/230C, again depending upon formula

• Inorganic coatings such as Inert Multipolymer Matrix, are also capable from cryogenic temperatures and up to 600C

These coatings when formulated correctly, using barrier pigmentation such as Micaeous Iron Oxide (MIO), aluminium flake or glassflake, will create a barrier to the ingress of chlorides to the stainless steel substrate.

There is also the matter of the insulation to consider when it is being used. It is well documented that with traditional insulation, and mineral based insulation with a metal jacket, that water will penetrate into the insulation system. The water will find a way through breakages in the metallic jacket or joints edges, and then it will soak through the insulation giving rise to CUI/CISCC conditions. Under certain operating conditions up to 177C, the traditional insulation could be replaced with a thermal insulation coating system (TIC) especially in the case where personal protection is required. This will remove the conditions which are required for CUI, and reduce the risk on CISCC, as no electrolyte is being held at the surface.

Therefore, a combination of a good barrier coating with high temperature resistance and a thermal insulation coating could be a very good choice in combatting both CUI and CISCC.

Neil Wilds, Global Product Director –

CUI/Testing, Sherwin-Williams, Protective & Marine Coatings.

Question:

Carbon capture and pipelines/storage – what are the limits of impurities when transporting CO2? PF

Answer:

Like many ‘Ask the Expert’ questions, there is no simple answer to this! Although general industry guidance on impurity limits is available from a number of sources [1-4], there are no internationally agreed specifications for CO2 composition during pipeline transport. Under current regulations, the responsibility lies with the pipeline operator to carry out their own assessment and specify impurity limits during the design phase of a given CO2 pipeline project. These limits can vary significantly depending on the composition of the CO2 stream, the economics of the purification technologies used and the operating conditions of the pipeline.

From a corrosion perspective, the most important impurity to consider is obviously water. When the water concentration is below its solubility limit in dense phase CO2 (~ 2500 ppm under typical pipeline operating conditions in the absence of other impurities) no corrosion will occur. However, the presence of other impurities can increase the likelihood of corrosive phases forming, either by reducing the water solubility or via chemical reactions between different impurities. Acid dropout is the most significant concern for pipeline operators, whereby highly corrosive aqueous phases, such as nitric and sulphuric acid, can form as a result of reactions between water, NOx, SOx, O2 and H2S impurities.

Assessment of the risk of water and acid dropout in CO2 pipelines due to the presence of multiple impurities is a complex process, which requires an understanding of the thermodynamics of fluid composition, the impact of operating temperature and pressure variations (including potential upset conditions) and interactions between impurities. The requirements for ship transport are typically more stringent than those for pipelines [5], with lowest temperatures representing the worst-case scenario.

Published corrosion rate data in the open literature should be treated with caution due to challenges in control of test parameters and the high degree of uncertainty around the correlation between laboratory test data and real world application. Combined with the relative lack of service experience in transport of CO2 captured from a range of industrial sources, this often leads to a degree of over-conservatism in materials selection. For CO2 specifications, thresholds in relation to acid drop out are set based on limited available data (often not lower than 25oC) and are therefore likely not conservative enough. The development of reliable standard test methods that are more representative of service conditions will go a long way towards addressing these issues.

A full description of the process for developing reliable CO2 impurity specifications for individual projects is clearly beyond the scope of this response but the interested reader is directed to the references below as a starting point.

References

1. DNV-RP-F104 – Design and operation of carbon dioxide pipelines, Recommended Practice, September 2021

2. Briefing on carbon dioxide specifications for transport, EU CCUS PROJECTS NETWORK, November 2019

3. DYNAMIS CO2 quality recommendations, EU DYNAMIS project D 3.1.3 report, June 2007

4. Materials challenges with CO2 transport and injection for carbon capture and storage, J. Sonke, W.M. Bos, S.J. Paterson, International Journal of Greenhouse Gas Control 114, 103601, 2022

5. Network Technology Guidance for CO2 transport by ship, ZEP/CCSA Report, March 2022

Gareth Hinds, NPL

Ask the Expert

The question in this issue features the type of coating needed for the internal protection of an above ground storage tank.

Question:

What type of generic coating is required to protect the inside of a tank containing a liquid with pH ranging from 2-13, and operating at between 65-80 C? PS PS

Answer:

The range of possible conditions covered make this a fairly difficult question to answer. When responding to queries where all the information required has not been provided, the specifier will need to err on the side of caution and generally ends up in the proposal being over specified in an attempt to cover the unknowns, in this case, in the tank. Over-specified linings generally increase cost and complicate application requirements. It is also the case that the more expensive a system is, does not necessarily make it a more suitable solution, as every lining has its own strengths and weaknesses.

The first question should always be what is the existing coating solution? If this is maintenance, what was previously used and was it successful? If it failed, do we know how and why?

Details of the chemicals involved, and their concentrations are required before a specification can be given, including durations in the different states (acidic and alkaline). Is the temperature a genuine continuous service temperature or are there short-term spikes to these maximums, or is the higher a design temperature (if achieved the lining is the least of the operator’s worries) and the lower the actual service temperature? What is the tank substrate, steel or concrete? All these will affect the lining selection.

With the wide range of pH quoted, this could be a neutralisation tank or pit and this type of aggressive service conditions often require a high build reinforced vinyl ester system. These systems are made up of a number of layers, including a trowel applied screed and glass fibre reinforcement mat to create a robust chemical resistant system, but the system cannot be confirmed until full details are known.

Matthew Fletcher, International Paint Ltd

Ask the Expert

The questions in this issue feature pipeline corrosion and how to decide whether a full repaint or sport repair is required for a failed vessel lining

Question:

What is Top of the Line Corrosion? When would you expect this, and how do you mitigate against it? BK

Answer:

Top of the line corrosion most commonly occurs in wet gas pipelines. It takes place on the top section inside the pipe (hence the name – top of the line corrosion) due to condensation of water containing corrosive agents, such as CO2 (‘’sweet’’ corrosion), H2S (‘’sour’’ corrosion) and acetic acid (HAc).

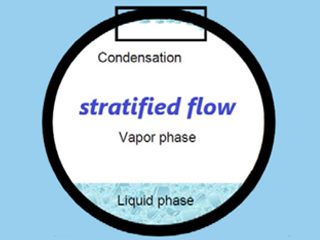

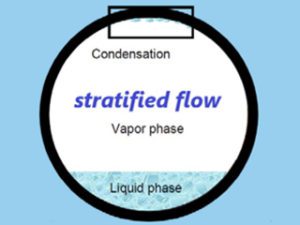

The flow regime has an impact on this mechanism, as it mostly occurs in pipes with stratified and wavy-stratified flow regimes – these allow for the condensation process to take place uninterrupted, and for that reason makes traditional liquid corrosion inhibitors not very effective in protecting against this type of corrosion, as liquids stay in the bottom area of the pipe and the protective film isn’t formed on top area of the pipe inner surface.

The factors impacting top of the line corrosion include:

– CO2 /H2S concentration

– Presence of organic acids

– Flow regime and flow velocity

– Temperature

– Pressure

– Water condensation rate

The mechanism of the top of the line corrosion in a ‘sweet’ environment, caused by the presence of CO2 is,

(a) Formation of aqueous CO2:

(b) Dissociation of H2CO3:

(c) Formation of H+ and CO32-:

The subsequent carbon steel corrosion mechanism involves,

(a) Anodic reaction:

(b) Cathodic reaction:

and the overall reaction is,

The presence of organic acids exacerbates top of the line corrosion as they lower the pH of the condensed water even further.

Top of the line corrosion can manifest itself as pitting, uniform corrosion, or mesa attack, and it depends on the above factors. To prevent top of the line corrosion, gas lines are often treated with a mixture of monoethylene glycol (hydrate inhibitor) and corrosion inhibitor. Monoethylene glycol is also able to reduce corrosion rate as it reduces the vapour pressure of the liquid phase of a wet gas.

The effectiveness of corrosion inhibitors in protecting pipes against top of the line corrosion varies and highly depends on the volatility of the chemical. You can find a variety of papers on this subject in NACE archive.

Suggested reference articles:

Dugstad, A., 2014. Top of line corrosion – Impact of MEG and organic acid in the gas phase. In: NACE International, Corrosion/ 2014, 9–13 March, San Antonio, Texas, USA, NACE2014-4382.

Ojifinni, R.A., Li, C., 2011. A parametric study of sweet top-of-line corrosion in wet gas pipelines. In: NACE International, Corrosion/ 2011, 13–17 March, Houston, Texas, NACE-11331.

Olsen, S., Dugstad, A., 1991. Corrosion under dewing conditions. In: Corrosion/91, Paper No 472, NACE, Houston, Texas

PN

Question:

What criteria should an inspector/owner use to determine whether to specify full removal or sport repair of a tank lining? PS

Answer:

There are many thoughts regarding the timing for replacement of vessel linings and whether it should be a total or partial replacement. Lining failures occur due to various mechanisms, the most common among others being the following:

• Blister formation due to osmosis through the coating caused by surface contamination on the steel substrate during preparation.

• Solvent entrapment in the coating

• Adhesive failure of the coating to the steel substrate caused by surface contamination, inadequate profile, material applied outside its pot life or incorrect ambient conditions.

• Explosive decompression where molecules of a substance that at the operating pressure are liquid but are gaseous at ambient migrate into the coating during operation but in a rapid shut down situation blow sections of the coating apart, this may take several cycles to effect this result.

• Thermal stress cycling, due to differences in the linear thermal expansion characteristics between the substrate and the coating, thermal cycling sets up a series of stresses which compromise the cohesive and adhesive strengths of the coating system.

• Mechanical damage from either internal or external sources

• Chemical attack of the lining due to the introduction of liquids into the vessel that destroy the coating integrity in either small or high concentrations.

The above list is not exhaustive, but gives a feel for the problems associated with vessel lining performance. Because of the potential for failures to occur during service, it is a bit of a lottery estimating the life expectancy of a coating system. A vessel operating at ambient temperature and pressure with a non-aggressive liquid will have a greater life expectancy than a similar lining exposed to varying temperatures and pressures with an aggressive mixture of liquids. Coating manufacturers on the whole will quote life expectancies for what they expect an ‘average’ exposure to involve.

When inspecting a vessel lining that has been in service for a period of time, any breakdown present needs to be carefully analysed to check whether it is a local failure with a driving force that is not uniform throughout the vessel, or whether what is encountered is the first stages of total lining failure. This can be a hard call for the inspector as the decision on whether a total reline, or a series of spot repairs, could lead to a premature/ catastrophic failure of the lining when put back into service especially when under pressure to get a vessel back in service as fast as possible.

From an inspection point of view, a lot depends on the inspector visually identifying the defects present. This should then be backed up by non-destructive tests to determine if the coating still meets specification – the most useful of these being to check the dry film thickness to look for wastage and coating thinning, and these need to be taken over the entire vessel, concentrating on the areas such as nozzles and edges where thinning of the coating is likely to be prevalent. Spark testing at 4Kv per mm of coating will show up any holidays along with other defects such as porosity and inclusions. Destructive testing such as dolly pull-off adhesion tests will give a good indication of any potential reduction in adhesion/cohesion but the test area requires to be repaired.

Spot repairing a vessel lining tends to be a short term fix as the repair itself can end up creating a weak spot. Preparation is invariably of a lower standard that that used to prepare a full vessel, ie power tool, which does not give a long term life expectancy for the lining. If blasting is used, it is essential to remove all corrosion salts and contamination from the affected area, chase back to a firm feathered edge. Spot repairs result in large amounts of ‘free’ edges where future breakdown may readily nucleate from. When blasting in a vessel to undertake spot repairs there will inevitably be collateral damage from the blasting operation in the form of overblast and ricochet which can lead to coating weakness and potential failure.

If a coating is reaching the end of its expected life it is not advisable to spot repair except in extenuating circumstances, as the failure rate will become unacceptable and damage to the vessel shell will occur. A new coating system should be used that will give the optimum life expectancy, consideration also to be given to the life of the vessel. Under most circumstances it is preferable to completely renew a coating system, changes in the operating parameters need to be taken into account as these may have changed since the original specification was drawn up, it is worth looking at failures and using these to learn from to improve the specification.

Bearing the above comments in mind, the following procedures and systems should be used:

• 100% visual inspection after clean out to identify through coating failures

• Dry Film Thickness check, all nozzles, edges and welds with at least 3 readings per m² to check for thinning/wear on the coating, minimum acceptable is 15% below specified thickness

• 100% holiday detection to find any pinholing or porosity defects

• Finally, if deemed necessary, apply dolly pull off adhesion tests to check for reduced adhesion of delamination.

• Report findings to client.

Under normal circumstances, a failure rate in the order of 15 to 20% or greater would be deemed as uneconomical to spot repair as the effort needed would be as great as that to recoat fully, the percentage being based on the percentage area of the vessel shell that will receive new coating, not the percentage area of visible failure or corrosion. What initially appears as a small defect of say nominally 10mm x 10mm will probably end up as a repair of the order 400 to 500mm diameter if done correctly.

Simon Hope, Auquharney Associates ltd

Readers are reminded to send their technical questions, for answer by the panel of experts, to the editor at, brianpce@aol.com

Ask the Expert

Question:

Under what types of exterior atmospheric exposure (other than marine) is it necessary to test for soluble salts before maintenance painting? PS

Answer:

The effect of soluble salt contamination on protective paint systems is well documented in terms of the acceleration of electrochemical corrosion processes and the propagation of osmotic blistering of paint films that are applied over salt contaminated substrates.

Paint specifications will normally define maximum levels for soluble salt contamination on a substrate. These can sometimes be set by an external specifying body (e.g., owner specifications, NORSOK, Network Rail, Highways England), or by the paint manufacturer.

Whilst the presence of a high level of salt on a surface might be obvious in a marine location due to the high levels of chloride in the atmosphere caused by saltwater spray, it is quite reasonable to expect salt contamination at an inland location. Industrial pollution is much reduced nowadays, due to tightening of air quality regulations, however considerable amounts of nitrates and sulphates are present in road traffic exhaust, and in addition large amounts of road de-icing salt are deposited throughout the winter months on the roads of all countries where winter freezing conditions may be expected. This salt is whipped up into a concentrated salt spray by the action of moving traffic on the wet roads which will deposit a persistent salt contamination that can spread some distance from the road on which it was deposited.

The simple answer to the question would therefore be that it is good painting practice to assess the surface salt level on any substrate that is to be painted, whether it be in a marine or inland location.

If the measured salt levels are low and meet the specification, then the project may proceed with occasional salt testing to ensure that the salt levels are still within specification. If local salt levels are high and exceed the specification, then the substrate will require fresh water washing and re-checking of the salt levels until the specification is achieved. In these contaminated locations then a more rigorous programme of washing down and salt level assessment must be agreed between the asset owner, painting contractor, paint manufacturer and independent inspectors.

Surface cleanliness is defined under the ISO 8502 series of international standards, along with equivalent standards from organisations such as NACE and SSPC.

ISO 8502 consists of the following parts, under the general title:

“Preparation of steel substrates before application of paints and related products — Tests for the assessment of surface cleanliness”.

— Part 2: Laboratory determination of chloride on cleaned surfaces

— Part 3: Assessment of dust on steel surfaces prepared for painting (pressure-sensitive tape method)

— Part 4: Guidance on the estimation of the probability of condensation prior to paint application

— Part 5: Measurement of chloride on steel surfaces prepared for painting (ion detection tube method)

— Part 6: Extraction of soluble contaminants for analysis — The Bresle method

— Part 9: Field method for the conductometric determination of water-soluble salts

— Part 11: Field method for the turbidimetric determination of water-soluble sulphate

— Part 12: Field method for the titrimetric determination of water-soluble ferrous ions

In addition, new ISO standards are under development to describe some of the other commonly used methods for determination of soluble salt levels.

Malcolm Morris

Ask the Expert

The questions in this issue feature preventing corrosion of rebars in concrete and when to test for salt contamination of a substrate before painting.

Question:

What is the best way to prevent corrosion of reinforcing bars in concrete? CL

Answer:

By far the best way to prevent corrosion of reinforcement is to ensure the design and construction is carried out correctly so as to achieve the required depth and quality of cover. The majority of reinforcement corrosion problems can be traced to poor design or detailing, lack of proper control of the concrete mix, its placement and curing, or mis-location of reinforcement resulting in low and inadequate cover.

Portland cement-based concretes protect reinforcement and other ferrous components by generating a low permeability and highly alkaline environment in which the steel protects itself through the formation of a stable passive oxide film. Provided these conditions are maintained then the steel remains protected. The cover can be thought of as a thick barrier coating that contains chemical species that actively protects the steel. In the early stages, the concrete cover can even heal itself if there are fine cracks resulting from shrinkage as the concrete completes its curing and reaches its full strength.

Continuing along the protective coating analogy, if the thickness is inadequate or the barrier is impaired in any way, then corrosion of the steel becomes a significant risk.

There are two main initiators of corrosion in reinforcement, chloride ions and carbonation. Above a certain critical level (which can depend on many factors) the reinforcement can suffer from severe pitting corrosion, even in the presence of high levels of alkalinity. Chloride ions can be present due to accidental contamination (for example, using unwashed dune sand), purposeful addition (until relatively recently, calcium chloride was widely used as a set accelerator), and through ingress from external sources such as marine environments and de-icing salts.

The other important cause of reinforcement corrosion is carbonation. This is where carbon dioxide from the atmosphere is able to enter the concrete cover and dissolve in the moisture present in the concrete to produce carbonic acid which in turn neutralises the alkalinity generated by the cement as it reacts and hardens. For a good quality concrete with adequate cover depth, this effect is slow and means the neutralised zone may not reach the depth of the steel for many tens or even hundreds of years. Where the cover concrete is of poor quality (for example, through the addition of too much water to the mix) or of inadequate thickness, then the time taken for the steel to be in neutralised concrete can be a matter of a very few years. Once no longer protected by the alkalinity, the steel can corrode in the presence of moisture, resulting in the production of expansive corrosion products and the subsequent cracking and spalling of the cover. If maintained in a dry condition (for example, indoor exposure) reinforced concrete can survive carbonation with little or no consequence.

Current standards and codes of practice provide the guidance required to limit the risk of corrosion from either chlorides or carbonation for a range of commonly encountered exposure conditions.

Where the exposure is particularly aggressive, such as offshore applications, additional measures may be required. The same approaches can also be used to reinstate the required durability of existing structures where it has been compromised through historic shortfalls in design, construction practices or maintenance.

The application of coatings to the concrete surface to resist chlorides and carbonation are widely used to extend the service life of existing structures, with periodic recoating further extending the time before further measures are needed. Should corrosion of the reinforcement have occurred then removal of loose and delaminated concrete, cleaning of the steel and reinstatement with fresh concrete (often a modified repair mortar with enhanced properties) can be effective for the treatment of carbonated or mechanically damaged concrete where chloride levels are low but are generally less than satisfactory where chloride induced corrosion has occurred.

Remediation of chloride contaminated concrete requires all residual chloride to be removed or, more practically, dealt with in some other way, such as by the use of corrosion inhibitors or cathodic protection. Corrosion inhibitors can be applied to the surface of the concrete and added to the repair mortar to enhance the ability of the fresh alkaline repair so it can better resist the ongoing influence of the remaining chlorides. Where the residual chloride level is too high for inhibitors to be affective or where a very long additional life is required, then cathodic protection may be the only viable alternative to demolition and reconstruction.

Cathodic protection, dating back to 1824 (coincidentally the same year Portland cement was patented), is widely used to protect buried or submerged structures such as pipelines, offshore facilities, and shipping but for many decades has also proved invaluable for the corrosion protection of steel reinforcement in concrete. Cathodic protection (CP) requires specialised design and should be carried out by suitably certificated personnel to ISO 15257: 2017 (see ICorr website for more details).

In summary, the best way to prevent corrosion of reinforcing bars in concrete is to keep them within a good covering of alkaline, chloride-free concrete. Where that is not possible, the build-up of chlorides and carbonation can be controlled by surface coatings, and steel that has already suffered corrosion can be rescued by returning it to an alkaline, chloride-free environment. Where that is not possible or practicable then additional measures can be taken to control the corrosion of the steel such as cathodic protection.

Paul Lambert